Pair Programming with Snakes

OK, this was supposed to be a longer post, but I'm trying to learn to get things like this out quickly, instead of yak shaving and eventually letting them fester in drafts. So, here we go. This one’s about pair development.

Pair Development is one of those habits that many of us practice in one form or another before realising that:

- people have already come up with a label for it (it's a thing)

- a significant amount of brain power has been spent turning it into a form of deliberate practice (it's a Thing)

This post lies somewhere between these two points. It's not an introduction to Pair Development, but a short description of a few dynamics that are often skipped during training, the things that we discover once we start practicing it ourselves. For tried and tested theoretical resources, check the footer.

So, if you came here for practical and opinionated pairing advice, and for snakes wearing fancy hats, you came to the right place, my friend.

First of all, why pair development?

Because while flow and being in the zone are all great things (I'm saying this without any sarcasm, believe me, I keep trying to make apps for that) interesting things happen when we're forced to verbalise our thinking process. This not only reduces an entire category of errors and improves knowledge sharing, but also—and I think this is crucial—it makes our code more a record of a conversation between two engineers rather than an internal monologue.

An Ideal Pairing day

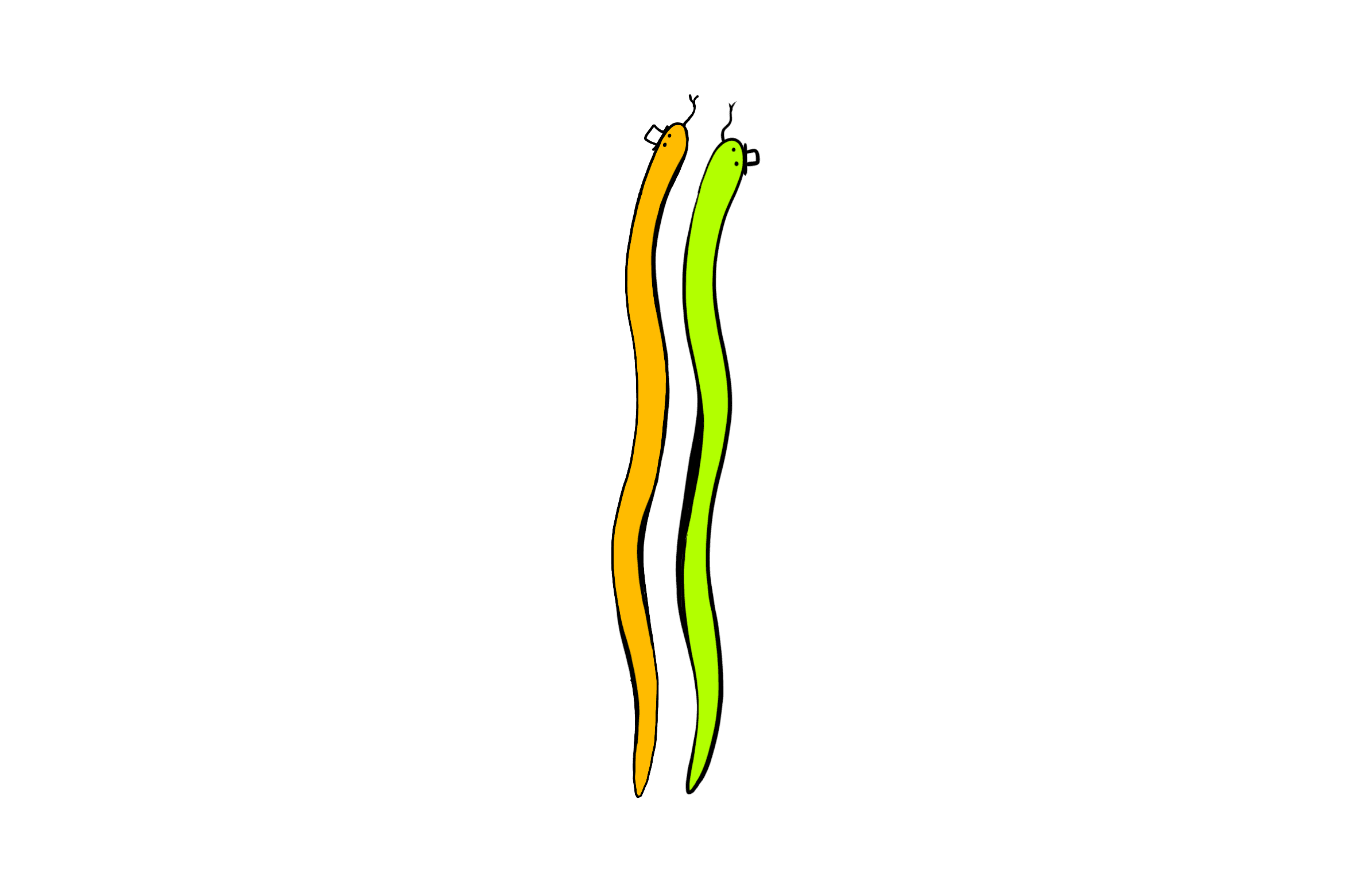

Let’s start with the ideal pairing day—two snakes work on a thing together. They might be using the same workstation, a remote editor or zoom and a bit of branch magic. The technology is secondary here and often the most rudimentary tools work best.

You might've also heard the term Ideal Pairing Day from a development manager, a “seasoned” engineer or a project manager. It was used as a measure of time: how much could two snakes achieve when pairing uninterrupted for a single day?

Keep in mind that “ideal” in this context means the same as “doesn't exist”. We’ll see why in a moment. On the rare occasions a day like this does happen, it might be a sign that you should be taking breaks more frequently.

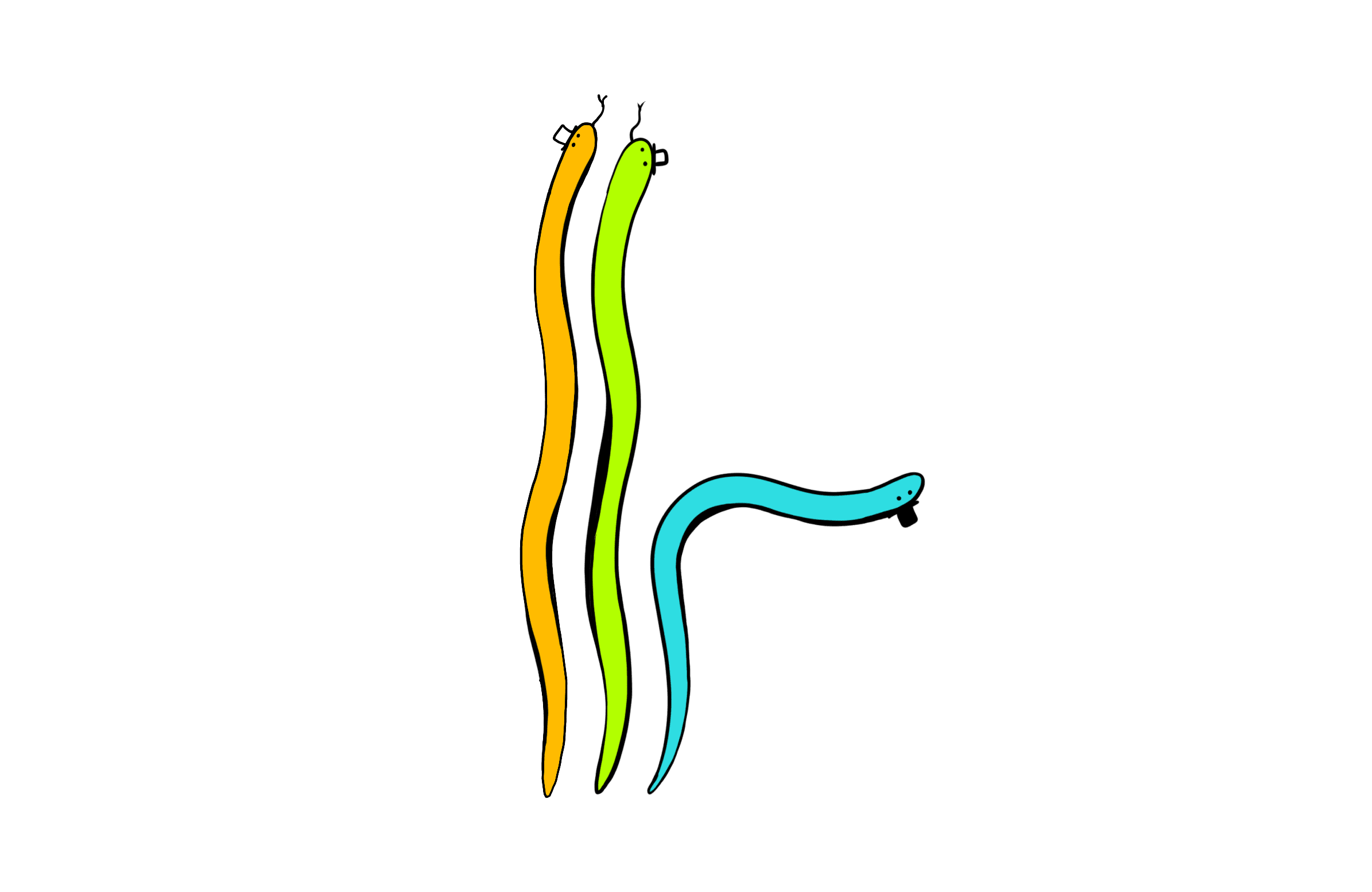

Less ideal would be ideal

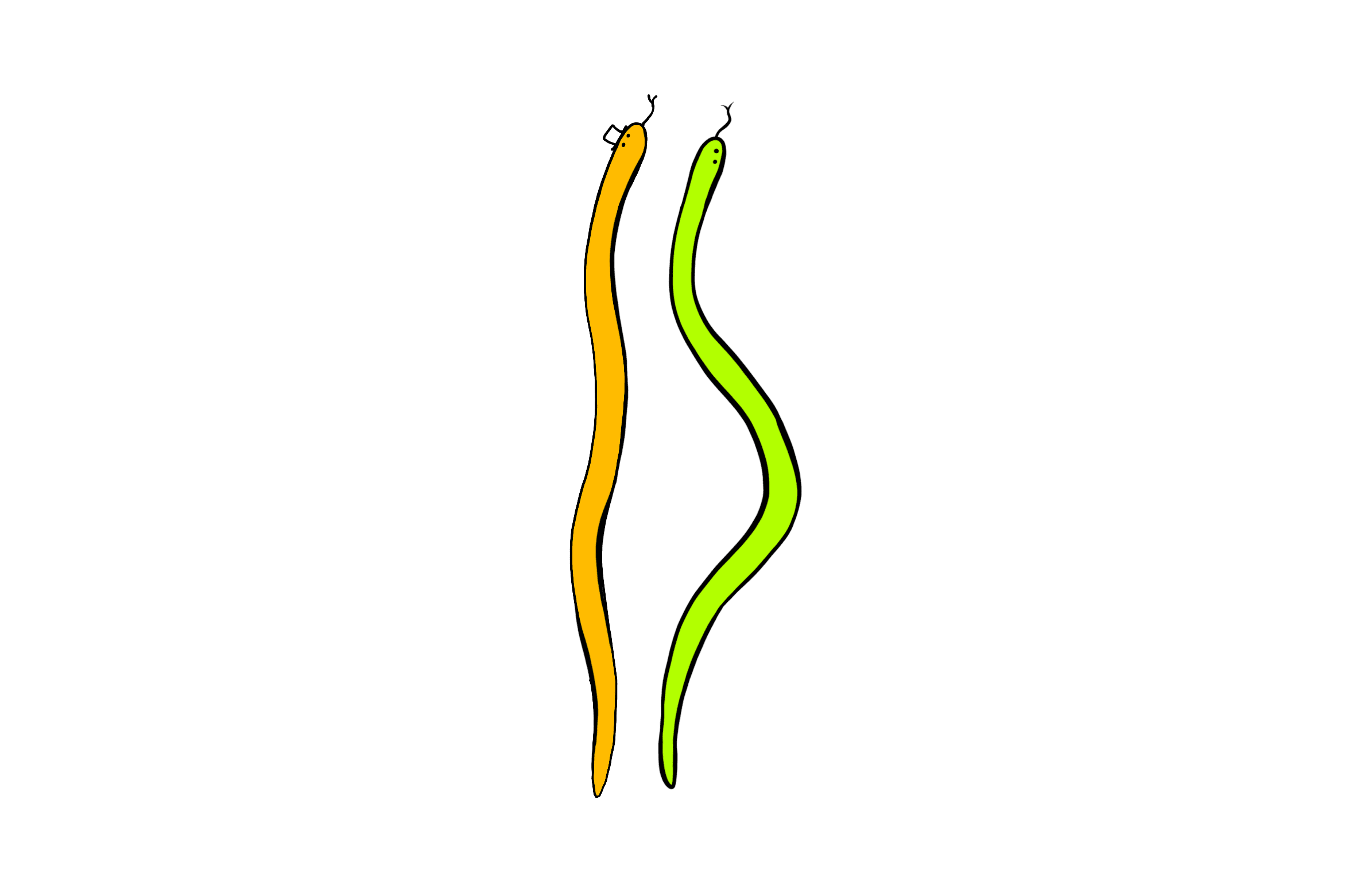

The yellow snake stays working on the story, cracking the red-green-refactor cycle like it's no one's business, but the green one moves temporarily to another task.

Why?

- You've been pairing for a couple of hours. You have a fairly clear idea of where you're heading, but then stumble upon a problem that needs more research. OR

- You realise you need to finish a smaller task that could easily be done in parallel. OR

- You're just tired of each other, tired of talking, or both.

All of these are valid reasons for one of you to move on to another task for a while.

So, you start out working on the same task, but eventually realise that splitting up would be the best use of your time. You have a fairly clear idea of the interface between the components you're writing and both pieces of work are not too complex.

After an hour or so you pair up again, connect the two pieces and continue working on the main problem with little difficulty. Happy snake times.

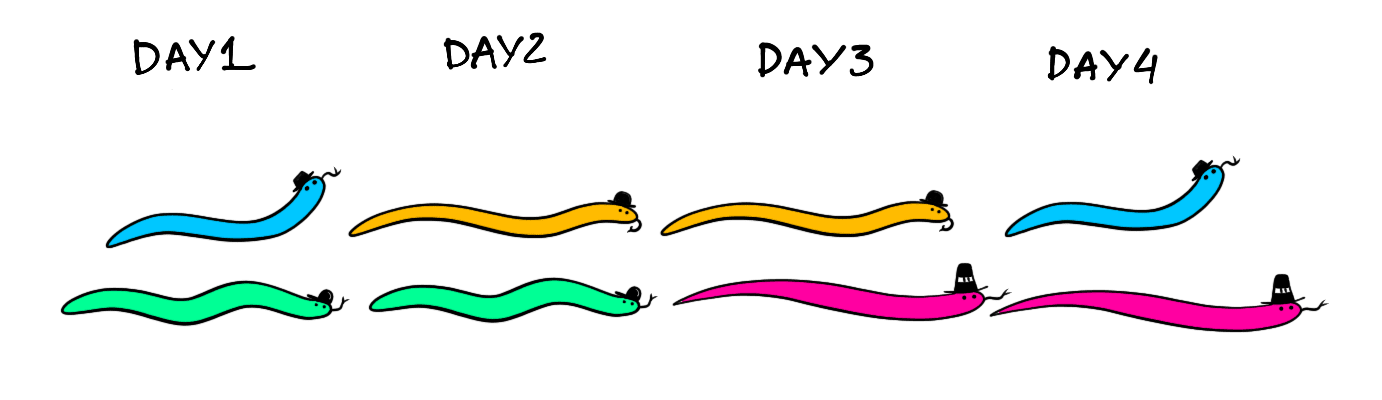

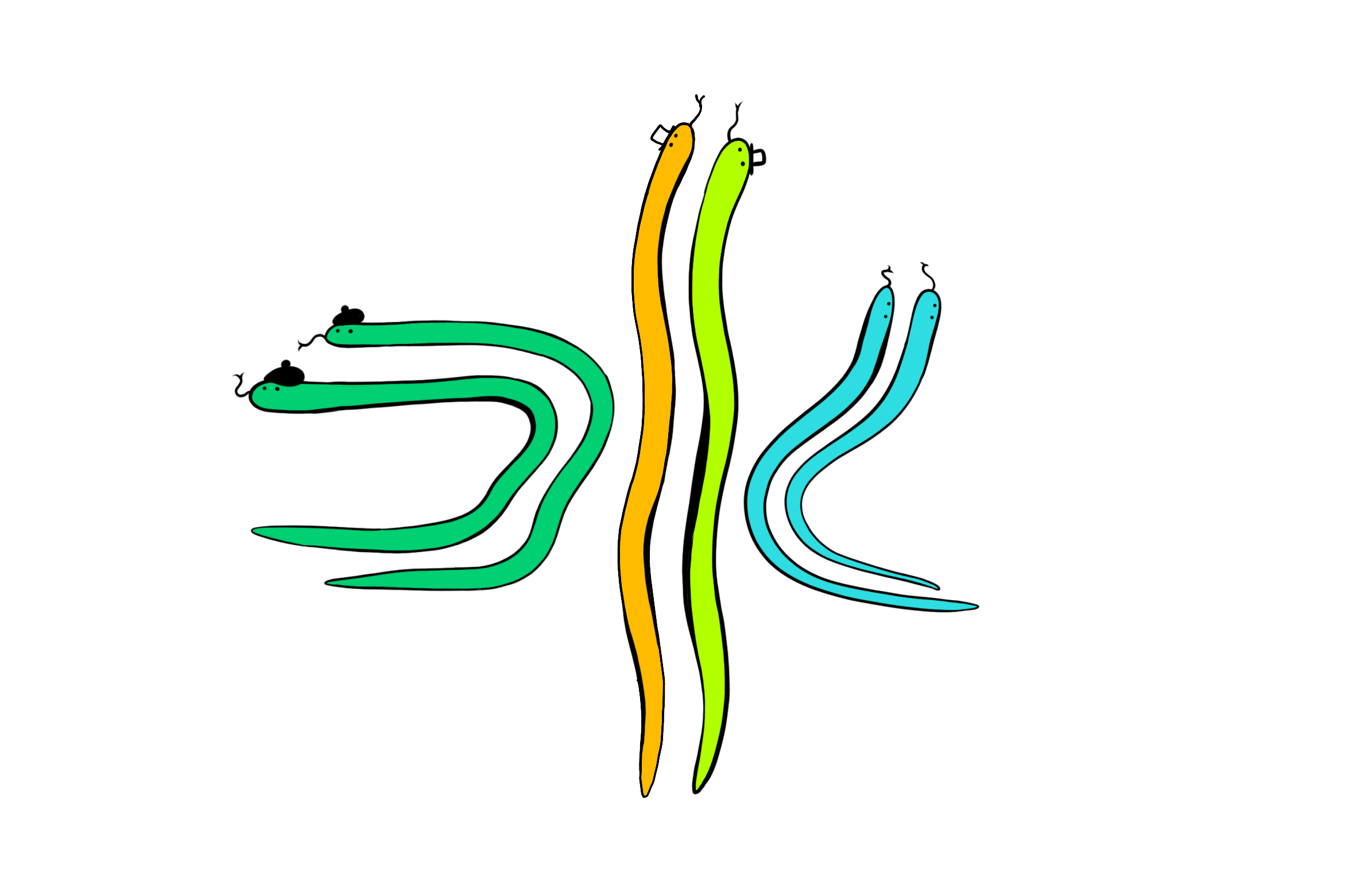

Rotations

Generally, the same snakes shouldn't be pairing with each other for longer than a day. Hence, just after the standup one team member is replaced by another. This cycle repeats the following day, creating a pattern like this:

Why do we do this? Frequent rotations help with knowledge sharing within the team and allow everyone to have a stronger sense of ownership over the project. No one wants to be "the postgres snake" for reasons that are purely circumstantial, such as just happening to be the original developer on a particular story. Same applies to the "exotic (database technology) snake" whom you have to call in the middle of the night because no one has enough context to revert a broken release.

Whether you're a reptile or a mammal, rotating can be a chance for you to either stay engaged or rest. You should avoid working on the same task for a week straight.

What about the downsides? These are pretty obvious, but often avoidable: frequent rotations can make it hard to keep enough context to feel that you're productive once you pick up the task again. It can be demoralising not to be able to immerse yourself in a problem fully. How to mitigate?

Some problems might just require more focused time, but this could also be a sign that the task should be split into smaller chunks. If you're sure that's not possible, consider having longer rotations or parallelising parts of the task. Avoid being dogmatic. Test and pick what works best for you.

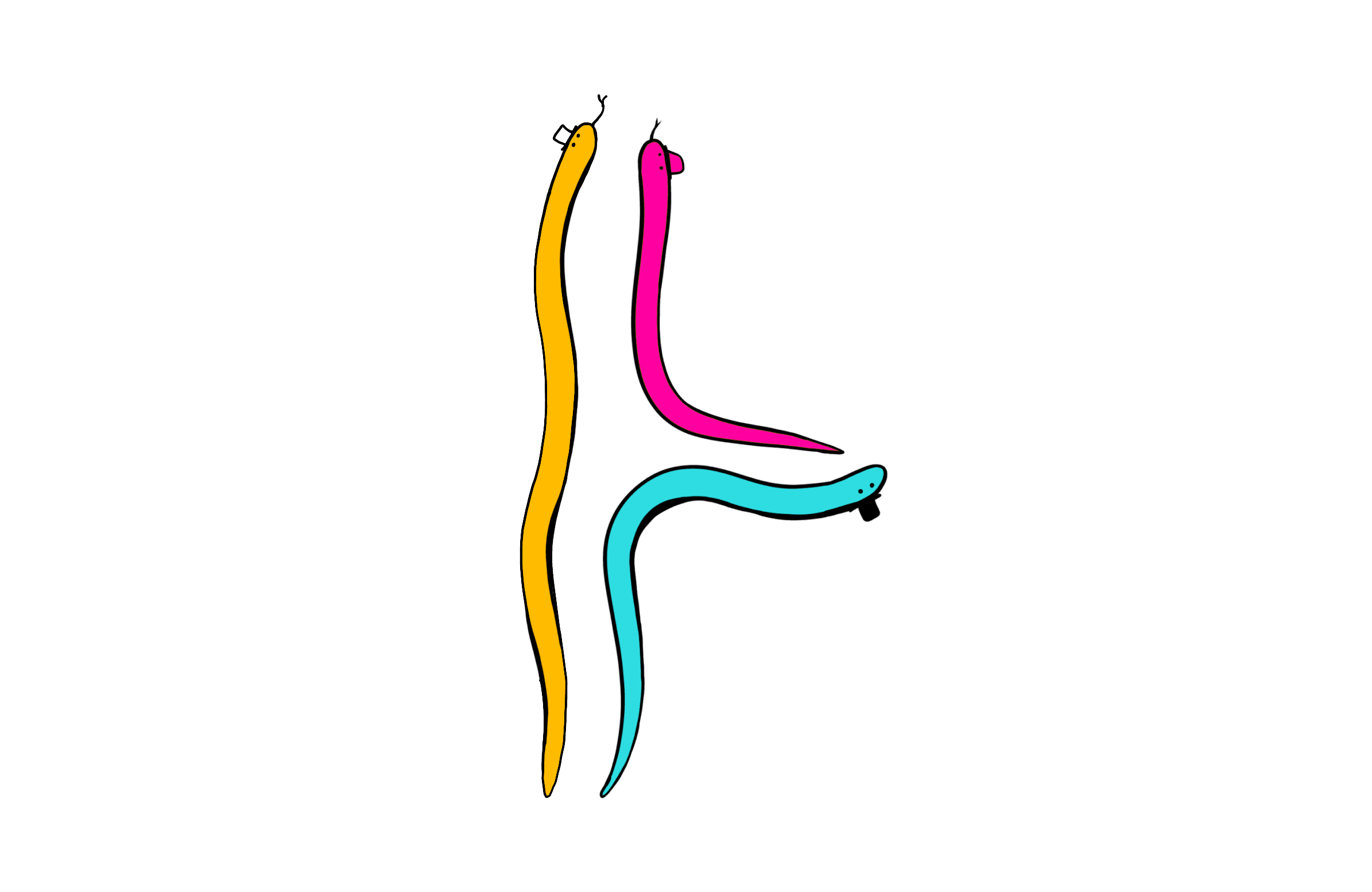

An impromptu mob

Yellow and Green had some difficulties with setting up the environment, so they got some help from a Cyan snake, one well versed in the pythonic scriptures. While Yellow and Green might not understand everything to the same extent as Cyan, at least now they know the required incantations. Her role here done, Cyan can now go back to her previous task.

Key points here: Cyan had the time to help, and gave them just enough context to continue working on the story. Maybe tomorrow Cyan will jump in and pair with one of them and learn more about their domain?

Multiple pairs joining

Here's where this comes in handy:

- Yellow and Green discover that their changes might impact a larger piece of work, or maybe they want to consult their approach with the rest of the team. OR

- Yellow and Green want to share with the rest of the team how to iterate on the large feature they're just wrapping up. There's no better way of learning than by practice, so all snakes briefly work together.

There's a third pair of snakes which we can't see here. Those snakes decided to avoid interruptions and work in a more focused way. If you feel like distractions are a big problem when pairing in your team, consider having designated “interruptible” and “uninterruptible” pairs.

A regular day

Yellow mobbed with an entire rainbow of snakes and moved on to working solo for a while. In fact, most of the snakes spent half the day on independent work, then joined back again in the afternoon.

Key points here: take frequent breaks, listen to your partner, and be present (no staring at your phone). Reflection on what works and what needs to be improved, deliberate practice—all of these things require our full attention.

Bless this mess.

I believe that the most valuable thing about pairing is the short feedback loop.

Here's why:

The two snakes split their thinking into two modes: the What? and the How? One of them deals with the short-term, tactical decisions while the other focuses on the long-term, strategic choices. They both have the same goal in mind but they see it through two different lenses.

Through pair development, their code becomes a record of the conversation between those two different perspectives, rather than the inner monologue of a single snake.

Think of the last messy piece of code you had to work with. Chances are that “internal monologue” would be a fitting description.

Credits and resources:

Alexandra Ciufudean edited this article and translated it into Human.

The inspiration for this post came from the diagrams created by my old colleague from Unruly, Gel Goldsby. I had so much fun writing this, thank you, Gel.❤️